Roman and Williams Buildings and Interiors was commissioned in 2014 by The Metropolitan Museum of Art to reenvision the permanent British Galleries, reopening in 2020, the year of The Met’s 150th anniversary. Roman and Williams founders Robin Standefer and Stephen Alesch were an underdog pick, and they competed over two years for prestigious 11,000-square-foot $22 million project, beating out over a half-dozen international architecture firms. Initially, the project was overseen by Ellenor Alcorn (now Chair and Eloise W. Martin Curator of European Decorative Arts at the Art Institute of Chicago) and Luke Syson (now Director of the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, United Kingdom) until 2019 when Sarah Lawrence and Wolf Burchard assumed the positions of Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Curator in Charge of The Met’s Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts and Associate Curator of British Furniture and Decorative Arts, lead curator for the new galleries respectively. The proposal that Luke Syson and Ellenor Alcorn made to museum leadership was a deviation from the usual script of royal patronage and country-house taste performed by many museums. Instead, they suggested an angle relevant to a younger, increasingly global audience: entrepreneurship, and the commercial drive that molded British art and design into a new consumer culture. “Robin and Stephen embody the notion of creativity within an entrepreneurial context,” says Syson. “Their work is how to make a space alluring and full of story, and that felt completely right.”

Roman and Williams undertook years of intense research, engaging with nearly every aspect of the space, from creating the fundamental architectural typology to conceiving and designing a new architectural environment to designing and detailing every case, platform, label, and pedestal as well as all the architectural bronze detailing and metal benches. Focusing on core themes of creativity and entrepreneurship, the galleries explore ideas around taste and how taste has always shaped and influenced culture. “We were interested in exposing this narrative with displays and installations, challenging ideas of public and private of mercantile and middle class of rulers and royals and how taste migrated from one to the next. We created dramatic artistic interiors to express 400 years of British decorative arts. There is now a logistical chronology from the Medieval Hall to the Tudors ending with the Victorians,” says Standefer.

When probes were done before demolition, they discovered that one of the exhibition rooms backed up to an access point in the Medieval Sculpture Hall, a popular thoroughfare of The Met. The layout was then reconfigured to make a new entrance, allowing access into a cozy, circa-1600 paneled home of a Norfolk merchant, with deep aubergine colored walls, the mood and lighting of the gallery is darker and evocative of the period. Here, the new entry into the British Galleries allows for a seamless chronological progression and introduces the architectural narrative, a story of arches through the eras that reinforce an understanding of geometries as they relate to changes in culture and artistic evolution.

Upon entering the 16th and 17th Century Gallery, the narrative is expressed with a series of compressed pocket galleries that lead to the Cassiobury Stair, a wonder of English Baroque woodcarving that’s been on view, but off-limits, since 1932. In a challenge to museum orthodoxies, it is now climbable—the first time in the Met’s history that an object from the British collection gets daily use. Roman and Williams also created a two-story facade of Tudor arches in plaster and framed in a bronzed metal to support an articulate, yet reductive architectural environment within the gallery and introduce a tactic seen throughout each subsequent gallery. Each of these arches holds a pocket gallery and evokes a domestic interior that punctuates, delights, and immerses the visitor in a very visceral experience. After climbing the Cassiobury Stair, which has been deconstructed at the second landing and met with a bronzed

metal mezzanine designed to allow a vantage point from the landing of a grand home of the remarkable tapestries on view. A fundamental principle of the design presents objects as they would have been seen and experienced, as they were meant to be used. This tension between treating the stair as an object of extraordinary carving, taking it out of domestic context, and at the same time keeping the domestic interior context that one can use and relate to is one of the key points in the design narrative Roman and Williams employed throughout the galleries.

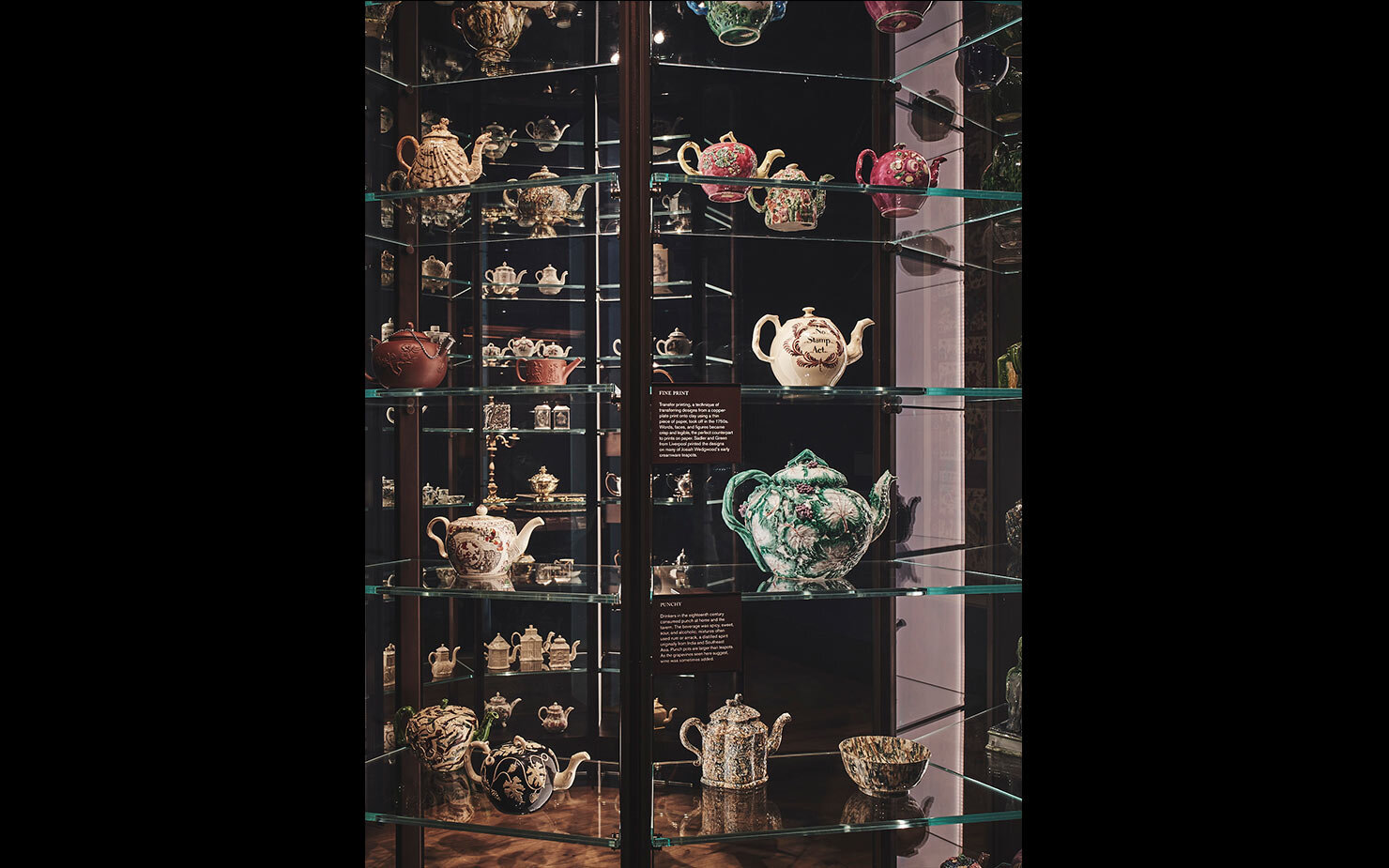

To tell the story of trade in the 18th and 19th centuries, 100 teapots were unearthed from storage and exhibited together in the round by shape and ornamentation, not date, inciting what Standefer hopes will inspire “object lust.” Displayed in a pair of ten-foot-tall semicircular cases, created by Roman and Williams, the installation evokes the feeling of being at sea with walls painted in ombre blue and echoed by a tapestry from India with handsewn boats. “Sometimes, you do want to see things that are not just the top 10 hits,” Alesch says. “People want to hear the outtakes. They want the B sides, the rough cuts.” “That was our eureka,” Standefer says. “And the Met went with us on that ride.” They persuaded curators that massing the teapots would tell a story of a different kind, one that featured a budding British pottery industry in competition to win business and please a new middle class with goods alternately ravishing, humorous, politically contentious or outright vulgar. “Our aim is to present British decorative arts, focusing on the ways craftsmen and manufacturers had to think outside the box, how to use new technologies, and how to market themselves. The galleries’ design creates an extremely stimulating new stage for our works of art to perform to their best of abilities and an excellent platform to shed new light on British art,” says Burchard.

The 18th Century is entered through a metal portal into a grand hall with two large arched facades holding three soaring Palladian arches signifying the Age of Enlightenment and covered in a heavenly pale grey lavender hue. In this grand hall visitors are welcomed into three 18th-century historic interiors where different seasons and times of day are simulated in two of the three historical interiors—a winter’s evening in the neoclassical Lansdowne House dining room, a summer afternoon at rococo Kirtlington Park, appropriate to when the rooms would have been used. A large window was added to view Croome Court to allow for transparency and light from the grand hall, as interiors of the era were traditionally dimmer.

Passing a threshold into the 19th Century via a beaux-arts-style arch (part of the Met’s original building, another demolition discovery) leads to the expressive and ambitious art trade brought about by the Industrial Revolution, presented in galleries that look to be lifted out of storefronts along London’s Regent Street.

The Chronology of Colors custom developed by Roman and Williams seen throughout the British Galleries focus on a moment in historic colors where traditional pigments, drawn from plant and other natural matter, were beginning to be synthesized with recent discoveries in chemistry and industry, resulting in an inventive and expanded range of palette that is highlighted throughout with the use of bronze.

The stimulating partnership between Roman and Williams and the Met’s curators appropriately mirrors the collaborative spirit that historically developed between British designers, makers, and retailers. With their lifestyle store, Roman and Williams Guild, this spirit manifests in a modern-day reality where they collaborate with artisans from all over the world, valuing unique handmade goods made with care and love for ancient technologies, mixed with contemporary innovation.